The Road to Antietam started at Manassas, where Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia badly defeated Union forces under John Pope on August 28 and 29, 1862. But Union forces retreated into the fortifications around Washington and reorganized under George McClellan. Lee could not hope to successfully attack McClellan’s much larger army in the extensive fortifications, and he could not afford to wait for McClellan to organize and launch a new assault.

On September 4 Lee began crossing the Potomac River into Maryland. The invasion of the North would force McClellan out of his fortifications. As a bonus Maryland, a slave state with several units fighting for the Confederacy, could provide recruits for Lee’s army. Lee believed he could strike across Maryland and into Pennsylvania’s Cumberland Valley before the slow-moving McClellan could challenge him. Lee would live off the rich northern countryside and the farmers of northern Virginia could bring in the fall harvest for the Confederacy.

But first Union troops in the Shenandoah Valley had to be dealt with, particularly the large force at Harpers Ferry. Lee launched a daring plan that split his army into several parts. “Stonewall” Jackson would make a wide sweep around Harpers Ferry to the west and meet up with two smaller forces that would surround it from the north and east. A small rearguard would screen the passes of Maryland’s South Mountain while part of Longstreet’s force would move toward the Cumberland Valley. It was a dangerous plan, but Lee knew his opponent and was betting the slow and cautious McClellan and his disorganized Army of the Potomac would not react fast enough to gobble up the widely scattered parts of Lee’s Army.

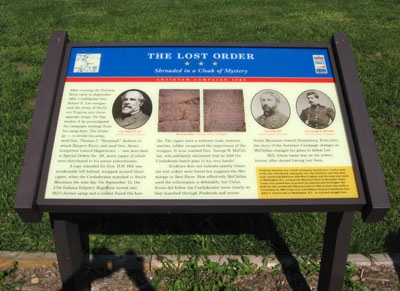

The Lost Order

Lee set out his plans in Special Orders No. 191, seven copies of which were sent out on September 9th to each of his division commanders. The plans were an intelligence gold mine that detailed the mission and timing for each of Lee’s units. Longstreet ate his copy after reading it. But somehow four days later the 27th Indiana Infantry Regiment moved into D.H. Hill’s former camp outside Frederick, Maryland and a copy of the plans was found wrapped around some cigars. The plans quickly made their way to McClellan.

The Lost Order wayside marker near the Visitor Center at Monocacy National Battlefield outside Frederick marks the approximate area where the plans were found.

Crossing the Potomac at Williamsport

By the time McClellan was celebrating his good fortune “Stonewall” Jackson was already across the Potomac River at Williamsport, Maryland and had driven the Union garrison at Martinsburg, West Virginia back into Harpers Ferry. Jackson had changed his march to make a wider swing to better scoop up the Martinsburg garrison, but it put him behind schedule in the overall plan. It was now a race – would Jackson capture Harpers Ferry before McClellan broke through the thin screen of Confederates on South Mountain to destroy Lee’s Army in detail?

The C&O Canal Aqueduct – Stonewall Changes Course wayside marker overlooks the Potomac where Jackson’s men re-entered Virginia from the north, having tried and failed to destroy the aqueduct bridge with artillery.

The Battle of South Mountain

On September 14 Lee’s badly outnumbered rear guard fought to hold the South Mountain passes against McClellan’s uncharacteristically rapid advance. Desperate fighting broke out at Turner’s Gap and Fox’s Gap in the north and Crampton’s Gap in the south. Casualties were heavy but the thin butternut line held out long enough to buy time for Lee to bring Longstreet’s men back from Hagerstown and for Jackson to finish his work at Harpers Ferry.

Today a small handful of markers and monuments are at the three passes through South Mountain. Although it was a sizable battle and very important to the morale of a Union army that needed a victory, it was overshadowed by the slaughter at Antietam three days later.

Harpers Ferry

There were almost 13,000 Union troops in Harpers Ferry, including the garrisons that had fallen back from Martinsburg and Winchester. By September 14 Jackson had placed 30,000 Confederates on the high ground all around the Union position. Jackson’s men were split, and had Union forces moved quickly through South Mountain they could have caused grave difficulties for the besieging Confederates. But before the slow-moving Union troops could arrive the Union commander, Colonel Dixon Miles, surrendered the town.

Today Harpers Ferry is a National Historical Park and the fields south and west of Harpers Ferry and the heights above the town where both sides manuevered have been preserved, with walking trails and many interpretive markers.

One of Lee’s Ammunition Trains

Halfway between Hagerstown and Williamsport, Maryland, a state historical marker, One of Lee’s Ammunition Trains, showcases one of the few Federal highlights of the Siege of Harpers Ferry. Told that Union commander Dixon Miles would surrender the garrison the next morning, cavalry commander Benjamin Davis insisted on trying to break out of the trap with his 1,300 cavalrymen. After a violent confrontation Miles gave grudging permission and Davis began a daring nightime ride through the besieging Confederate troops and north through Sharpsburg and onward.

Not only did Davis succeed in bringing his men to safely across the Pennsylvania border, he managed to intercept and capture a wagon train of 40 wagons of reserve ammunition for Longstreet’s command on the way. A Mississippi native who had stayed loyal to the United States, Davis used his accent and the darkness to assign his troopers as escorts for the Confederate wagons and divert them down the road to Pennsylvania, a ruse that wasn’t discovered until daylight.

The Battle of Antietam, or Sharpsburg

After being thrown out of the South Mountain passes Lee took up a defensive posiiton near Sharpsburg along Antietam Creek and waitied for Jackson to join him from Harpers Ferry. McClellan’s forces arrived before Jackson with three times Lee’s numbers but, suspicious of a trap, he delayed his attack until most of Jackson’s men arrived.

On September 17 at the Battle of Antietam they fought the bloodiest single day in American history. The two armies combined suffered 23,000 casualties.

The Battle of Shepherdstown

On the day after Antietam Lee’s army held the field until nightall, then withdrew across the Potomac at Boteler’s (or Pack Horse) Ford. Pendleton’s Reserve Artillery supported by two badly depleted brigades of infantry held the bluffs above the ford while the rest of Lee’s forces began to march north to recross the Potomac at Williamsport and – he hoped – resume his invasion of the North.

Union forces crossed the ford in strength the next day. Pendleton showed up in panic at Lee’s Headquarters reporting the loss of all the Reserve Artillery. But A.P. Hill’s Division returned to the ford, driving the Federals back and saving most of the guns. Three markers commemorate the battle on the south bank of the Potomac at the ford.

Lee realized that the nearly continuous heavy fighting of the summer culminating in the slaughter of Antietam had left his army in no condition to continue the offensive. The men heading to Williamsport were recalled. The first invasion of the North was over.